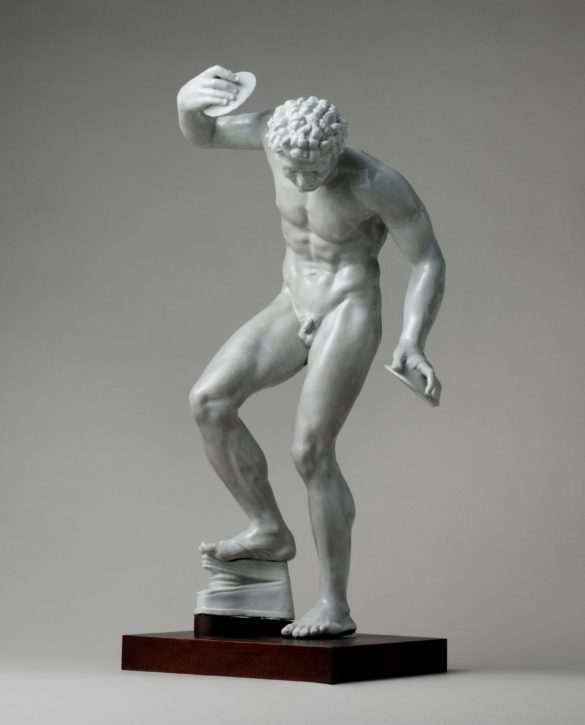

ITALIAN MAIOLICA

All Italian pottery covered with a white, tin-opacified glaze made during the Italian Renaissance in centres at Urbino, Deruta, Caffagiolo, Faenza and elsewhere, is known as ‘maiolica’. The term ‘maiolica’ was originally used in fifteenth-century Italy for lustrewares imported from Spain. Italian maiolica is celebrated for its colourful, painterly tradition. The images were drawn from printed sources, often scenes from classical mythology or daily life. Few examples are signed; however, one of the greatest painters did sign his work, Francesco Xanto Avelli da Rovigo (c. 1487-1542).

Plate with the Abduction of Helen, painted by Francesco Xanto Avelli (c. 1487–1544), tin-glazed earthenware, Italy, Urbino, 1534. (The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Inv. no. 84.DE.118)