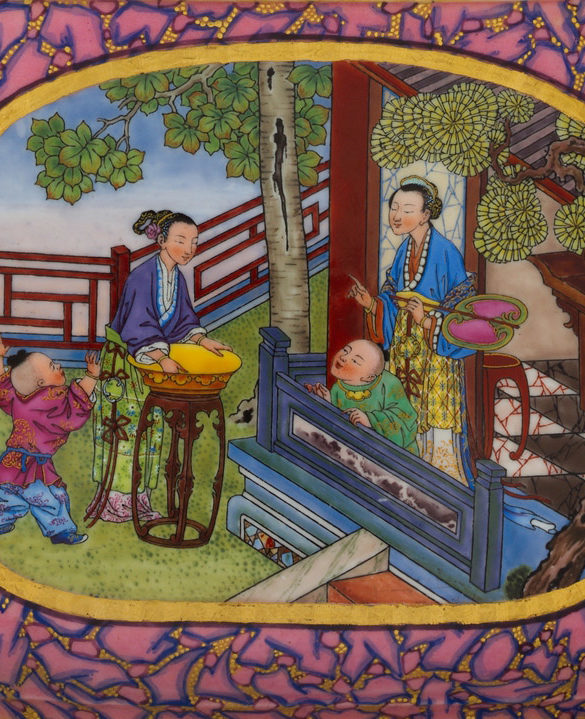

FLOWER PAINTING

From its inception, flower painting was part of the manufactory’s stock repertoire. In the 1740s, a newly hired fan painter was sent to Paris by the factory, then based at Vincennes, to study flower painting on Meissen porcelain. In addition to print sources, they must also have copied fresh flowers. Many of the factory painters were adept at working in a number of genres with flower painting being but one of their skills. One of the most talented flower painters at Sèvres was Edme-François Bouillat père (active 1758–1800), who was responsible for the ribbontied bouquet on this rectangular plaque, a type frequently mounted on furniture made during Louis XVI’s reign.

Sèvres plaque from drop-front desk (secrétaire à abattant or secrétaire en cabinet), painted by Edme François Bouillat père, c. 1787. (Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Samuel H. Kress Foundation, 1958, Inv. no. 58.75.57)